William Grant Turnbull

Sculptor

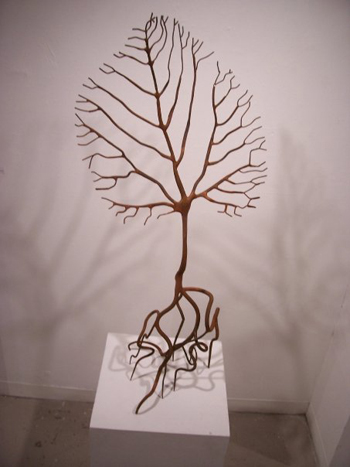

William Grant Turnbull has spent the last decade focusing on all forms of metalwork – from state of the art welding techniques to traditional blacksmithing – in order to become a successful public sculpture artist.

Since earning his MFA with a focus on public sculpture in May 2008 from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Turnbull established a fabrication, prototyping and artist-supply business – 11th-hour Heroics, LLC.

He has continued to pursue public art and is currently a member of the Wisconsin Arts Board Percent-for-Art mentorship program.

Turnbull's work explores the intersection of themes including traditional agriculture, gardening, botany, entomology and the tools that make those pursuits possible.

"I sculpt allegorical hybrids that appear as cross-pollinations between forms found in nature and methods of industry. I believe that a bio-mimetic approach to design is the most effective and elegant solution to any visual or engineering problem."

Turnbull grew up in South Florida and earned a BFA in art and art history from the Kansas City Art Institute. He has lived and worked in Madison since 2004.

The loading dock to the UW-Madison Art Department’s sculpture foundry hangs open on a particularly snowy, blustery January day. Inside, the furnace belches and the radio blares, stoking the intense atmosphere that surrounds the equally intense sculpture artist who made this his second home during grad school.

Amid piles of 2,300 quarter-inch steel rods stands 6-foot-1 William Turnbull, an imposing figure clad in a long leather apron, thick work gloves, safety goggles and a massive helmet to protect him from the orange-hot sparks spewing around the room.

Over a nearby stool hangs a brown suede jacket, with “Turnbull” spelled out in studs across the back with more studs arranged in the shape of a bull’s head on one shoulder. Befitting his family name, the sculptor charges forward, undeterred by numerous obstacles at every turn, in his goal to create a piece of public art he has envisioned for the past two years.

Despite his tough, almost-intimidating presence, the 27-year-old artist turns out to be an easygoing chatterbox, engaging and warm. He talks about his sculpture with awe and pride not unlike a new father.

With help from friend and colleague Alex Wong, Turnbull set out nearly two years ago to create Flowfield – a bio-mimetic field of naturally-oxidized steel wheat filling a long-vacant Humanities Building rooftop deck.

Flowfield is Turnbull’s response to the increasing mechanization of the farming industry and marginalization of the independent blacksmith.

“In our mad dash to populate the planet, we have made it absolutely necessary to mechanize agriculture. An awful staggering loss of life would result if it were not for this trophy of human ingenuity,” Turnbull says in his M.F.A. project statement. “All the technical advances, new alloys, new tools, are illusory advances; no longer is the local ironmonger forging swords and plows to hold onto what little settlement humans had.”

The industrial process required to produce Flowfield also reflects Turnbull’s concern about the conflict between the outsourcing of manufacturing that once provided this country’s economic stability and the means and work ethic that is the basis of that industry to which our society still clings.

“Every stalk specimen in Flowfield was fabricated, mass-produced and stamped with the efficient grace of a well-oiled machine. And just like contemporary agriculture, it is functionally elegant and effective, but once again, highly forced,” Turnbull says.

Soon after enrolling in the M.F.A. program three years ago, Turnbull began eying the rooftop space for an installation, but didn’t come up specific plans until the following year.

On the day he finally was allowed to visit the courtyard, he was struck by its gusty conditions and thought: “What can I do that uses wind?”

He came up with an answer by reflecting on road trips through Midwest, where he saw the ubiquitous “amber waves of grain.” Just as wheat fields turn golden in the summer, Flowfield’s kinetic stalks of steel turn a gold-orange from exposure to the elements.

Negotiating the right to public art

Anyone who’s been to the upper floors of Humanities can’t help but notice the perpetually fallow rooftop courtyards, originally designed for large art installations.

Wide metal bridges extend from each end of the sixth floor hallways to the courtyards, hinting at public access but perpetually locked to all but a few – including, during a recent six-month period, Will Turnbull.

“The impetus behind the piece was to make this (rooftop) a public space again,” Turnbull says.

“Now they have an excuse to come out here,” he says during a work break in early May when he put the finishing touch on the installation — placing tubes of red-orange neon under the perimeter of the roof’s ledge.

“Flowfield is my attempt to bring an agricultural logic to a building designed to segregate us from the rest of the campus and remind us all that we must matter to someone outside these walls,” he says in his project statement.

He overcame several logistical hurdles, with persistence, patience and a lot of paperwork, which started well before he began to build the steel wheat.

When considering proposals to use or occupy campus rooftops, terraces and similar spaces, facility managers must ensure human safety and protect the building from damage.

The dangerously low ledge around the courtyard has been a deal-breaker in previous proposals to use the space for installations and much of the reason why the terrace has been locked. Flowfield’s design — 2,270 steel stalks welded together at the bottom — prevents visitors from getting near the edge, thus allaying safety concerns.

“A grid based upon the geometry of the courtyard serves as the pleasing shape of the composition, but it was its function as a fence that allowed this piece to administratively and financially happen,” Turnbull says in his project statement. “The approval process was lengthy and slow. It drew on reserves of patience and diplomacy that I did not know I possessed when the idea for a wind-powered kinetic sculpture on the roof came to me two summers ago.”

The Humanities rooftops used to be considered a form of “terrace” and have a history of use by the Art Department, but enough problems arose to prompt campus facility officials to permanently lock it up.

“We don’t just let people go out onto what is perceived as a rooftop deck,” says John Paine, associate director of facilities for the School of Education.

Proposals need to include detailed plans, a layout of what will be and/or happen there and how safety will be handled, Paine says.

Three years ago, an art student wanted to create a piece for one of the courtyards but she soon gave up the idea, likely because of the detailed application procedure, Paine says.

“Will (Turnbull) was persistent and we made it happen,” he says.

Graduate school gives artists the chance to professionalize while they still have something of a safety net, Turnbull says.

“Failure is nowhere near as bad as not asking for something,” he says. “Sometimes you hear ‘no’ but, occasionally, asking is really great because it’s a ‘yes.’”

Using the space for an art project doesn’t have to be rare opportunity if the artist demonstrates responsibility, has a well thought-out plan, is willing to do the footwork and accept parameters such as leaving it clean and undamaged, Paine says.

“(Turnbull) did a good job of all that and signed a user agreement,” Paine says. “I think it’s important that this campus make every reasonable effort to accommodate and facilitate requests like this.”

The relatively inhibitive process for using the rooftop courtyards speaks to the need for more outdoor display space for student artwork on campus and specifically in the vicinity of the Art Department, he says.

While seeking site clearance, Turnbull also needed to secure project funding. He played a careful juggling act between assuring the university that he had the funding while also promising the Madison Arts Commission that he would obtain permission to install the project he was asking them to help fund.

Turnbull took out a $2,400 student loan for materials to supplement the $1,500 BLINK grant for temporary public art projects that he received from the commission, “which helped a lot in the end,” he says.

Turnbull’s detailed grant application fit the site-specific, temporary requirements of BLINK and “visually, it’s a very exciting project and a good use of space,” says Leslee Nelson, a member of the Madison Arts Commission.

Turnbull first spelled out his proposal for Flowfield in the grant-writing course taught by Nelson, a mixed-media professor in the Art Department. She sees Turnbull’s project as “unique, major and significant.”

“I think it’s a wonderful addition (to the rooftop),” she says. “I’d say it was fairly pioneering… I was surprised he actually did it.”

She likens Flowfield to Christo’s wrapped buildings and landforms, in which a significant part of the project involved dealing with bureaucracies and “the memory of them existed even though the reality was gone… (Flowfield) is the kind of thing people are going to be talking about.”

More delays and obstacles

Turnbull also faced a series of physical and material constraints on the project timeline.

The university’s local steel supplier doesn’t stock four and a half miles of quarter-inch rod, so the materials had to be special-ordered from a company in Chicago.

But Turnbull was told that his shipment had been delayed while the manufacturer filled a material order for the new I-35 bridge in Minneapolis to replace the one that had collapsed.

Turnbull and Wong also had to create many of the specialized tools they needed to build Flowfield. This included a wavy iron stamp to forge the tops of the steel rods into a grain-like texture and a wooden tray to create the base grid that holds the stalks together.

Artists often run into the need to invent tools out because the creative process and the pursuit of a final piece require it, Turnbull says.

“A lot rests on the artist to create the technology for their own tools,” he says. “They don’t come up with things that are gonna save the world but they ask the right questions.”

Successful, established artists often can hire engineers to do that, but not students. So Turnbull’s work experience in the construction and home furnishing industries came in handy.

True to their studio business name – 11th Hour Heroics – Turnbull and Wong worked up until last minute before the M.F.A. show opening in order to fill and install the neon tubes that illuminated the steel field from below.

“Aesthetically, the piece works within that space,” says sculpture professor Truman Lowe, Turnbull’s M.F.A. advisor.

Lowe says Flowfield succeeded because Turnbull created it for a specific site, incorporated his interests in ecology and the environment, and overcame the obstacles that stemmed from working with a large public institution.

He says Turnbull handled the confinements and challenges of creating public art maturely — writing grants, figuring out materials, dealing with outside companies and institutional rules.

Lowe took a hands-off approach, even when Turnbull sought advice on problems that arose.

“I wanted him to solve them, and I knew he would,” his advisor says. “The success of the piece was his ability to respond to (those problems).”

Lowe credits Turnbull’s intelligence and range of skills for enabling him to create a great piece in short time.

“What crystallized for me — the point of how it all came together here — is to learn to be good decision maker… This entire project can be broken down to that,” Turnbull says.

Turnbull, who received his M.F.A. in May, is still seeking a permanent home for Flowfield – “a prairie that wants a crop circle,” he half-jokingly suggests. But he’s willing to break it down and recycle it if necessary because “there’s a fine line between public art and heavy litter.”

— by Rebecca K. Quigley

© William Grant Turnbull 2009